1. The Wrong Guitar for the Right Idea

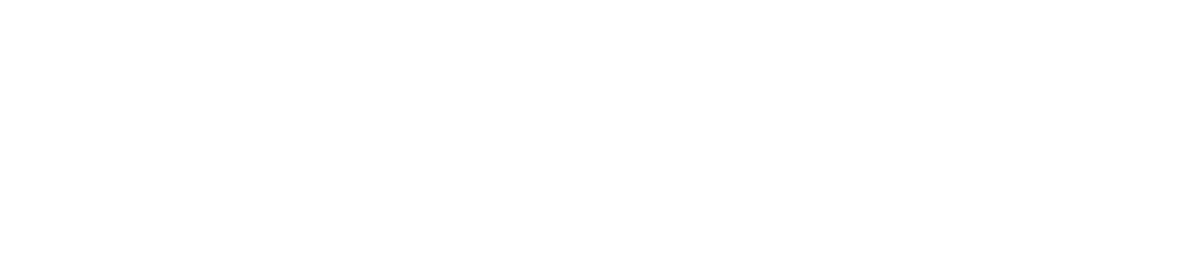

When Leo Fender unveiled the Jazzmaster in 1958, he was trying to move Fender up the musical food chain.

The Telecaster had conquered country. The Stratocaster had seduced rock and roll.

Now Leo wanted jazz players - the serious, respectable crowd - to take Fender seriously.

Everything about the Jazzmaster was aimed at that market:

A warmer, smoother tone than the Strat.

A more ergonomic offset body for seated players.

A dedicated rhythm circuit for darker comped chords.

It was marketed as Fender’s “most advanced guitar for the serious musician.”

It was also a commercial failure with its target audience.

Jazz players hated it.

Surf guitarists made it immortal.

2. Pickup Physics: Wide Coils and the Pursuit of Warmth

At the heart of Leo’s plan was a new pickup design.

The Jazzmaster pickup looks like a P-90, but its internals are completely different.

Instead of tall, narrow coils like a Strat, Leo used wide, flat coils wound pancake-style to around 8.0 kΩ.

That geometry changes everything:

A wider magnetic aperture “hears” more of the string’s length.

This averages out higher harmonics and smooths the tone.

The pickup’s resonant peak drops from roughly 2.3 kHz (Strat) to ~1.8 kHz.

The result is a rounder, mid-forward sound with less bite.

In modern EQ terms, Leo built a Fender that behaved more like a Gibson neck pickup.

3. Scale Length and String Tension

The Jazzmaster’s 24.75 inch scale was a deliberate break from Fender tradition.

That is the same scale as a Les Paul, not a Tele or Strat.

A shorter scale reduces string tension by about 7 to 8 pounds per set, giving:

Softer feel and smoother bends

Slightly slower transient response

A warmer overall tone

Leo assumed jazz players wanted a forgiving touch rather than the snappy response of a Tele.

He was right about the physics, but wrong about the audience.

4. The Bridge and Tremolo: Engineering by Accident

Then came the most controversial part of the design: the floating tremolo system.

Unlike the Strat’s synchronized trem, the Jazzmaster’s tailpiece sits far back on the body.

Strings cross a rocking bridge with only about a 6° break angle.

Two big consequences followed:

String instability - the low break angle meant less downward pressure, and strings could pop from saddles.

Behind-the-bridge resonance - the long section of string between bridge and tailpiece vibrates sympathetically, producing metallic overtones between 1.2 and 2.0 kHz.

Leo tried to mute this with a screw-on bridge cover (the “ashtray”).

Surf and indie players later discovered it was the best part of the sound.

Every famous Jazzmaster overtone began as an engineering flaw.

5. The Rhythm Circuit: Built-in EQ Preset

The upper horn housed a separate rhythm circuit with two roller knobs and a slide switch.

When engaged, it bypassed the main controls and used only the neck pickup, but through a 50 k tone pot and 1 M volume pot.

That 50 k tone control heavily loads the pickup, rolling off much of the treble.

The result is a dark, woody tone with a low-pass cutoff around 2 to 3 kHz - perfect for comped jazz chords.

Flip the switch down and you are back in “lead” mode, with both pickups running through normal 1 M pots.

Leo effectively built a passive EQ preset system years before active tone shaping existed.

Players just found it confusing and mostly ignored it.

6. Body Shape and Resonance

The offset-waist body was not just aesthetic. Fender patented it for ergonomic reasons, claiming it was more comfortable for seated players.

The larger body also adds low-mid resonance between 100 and 250 Hz, giving the Jazzmaster a more “acoustic” response when played unplugged.

Combined with the shorter scale and lower tension, it creates a guitar that sustains longer and blooms softer than a Strat or Tele.

Less bite, more body.

7. The Great Irony: Jazz Rejected, Surf Adopted

Despite its name, the Jazzmaster found no love among jazz musicians.

They wanted hollow bodies, not futuristic slabs with chrome switches.

By 1962, another scene had discovered it. Surf guitarists.

What jazz saw as flaws became surf perfection:

The floating trem made watery vibrato possible.

The shallow bridge angle added that metallic “drip” under spring reverb.

The plunky short-scale attack gave percussive precision at high speed.

Leo designed a guitar for dark clubs.

It found its home on bright beaches.

8. Measured Tone Differences

For the data-minded:

Lower Q-factor, lower peak, wider bandwidth.

It records beautifully because it never slices through the mix.

9. From Surf to Sonic Youth

After the 60s, the Jazzmaster faded from Fender’s catalogue.

Then in the 1980s, a new kind of guitarist revived it: the experimentalists.

Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo used the behind-bridge resonance as a texture.

Kevin Shields used the trem’s looseness for his “glide guitar” technique.

Nels Cline brought it full circle, using it for modern jazz.

Every one of them exploited a property Leo had tried to suppress.

The Jazzmaster became a feedback instrument as much as an electric guitar.

10. Failure by Design

Leo Fender built the Jazzmaster to sound civilised.

Musicians made it sound dangerous.

It was rejected by the people it was designed for, then redefined by those it wasn’t.

Few instruments embody the concept of creative misuse as completely.

Every design flaw is an invitation for someone else’s idea.

TL;DR

Wide, low-inductance pickups gave a warmer tone.

24.75” scale reduced tension and softened attack.

Floating trem and shallow break angle added harmonic overtones.

Rhythm circuit acted as a preset jazz EQ.

Jazz ignored it. Surf and indie made it iconic.

Epilogue

The Jazzmaster is not a jazz guitar.

It is an experiment in tone physics that escaped its purpose.

Leo Fender designed warmth.

The world heard shimmer, chaos, and reverb.

And that is how failure built one of the most versatile guitars ever made.