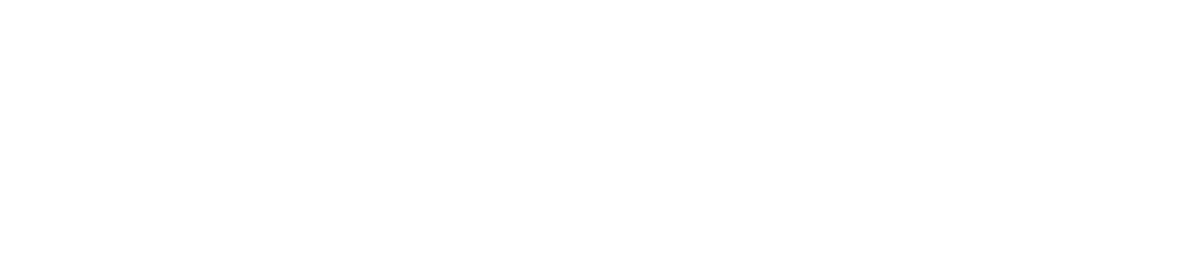

Every guitarist knows the Gibson PAF humbucker: the warm, fat, noise-free pickup that rewrote the sound of rock and jazz after 1957.

But three years earlier, Seth Lover and Gibson quietly launched something far stranger: the Alnico V “Staple” pickup.

It was a technical stepping stone. It was a tonal experiment.And it vanished almost as soon as it appeared.

Let’s dig into why, but before please hit subscribe!

1954: A New Kind of Custom

In 1954, Gibson introduced the Les Paul Custom: the so-called “Black Beauty.”

It was pitched as a more refined, jazz-leaning sibling to the Goldtop. Jazz players wanted smoother bass and a clearer <a href="why-i-do-not-have-a-stiff-neck">neck</a> position.

The solution? A pickup unlike anything seen before.

Instead of screws acting as pole pieces (as in a P-90), the Staple had individual Alnico V bar magnets sitting under each string.

They looked like little metal staples, flush with the cover.

Each one was magnetised separately.

This was Seth Lover’s idea: to focus the magnetic field more tightly around each string.

How It Worked (and Why It Mattered)

The design gave the Staple a fundamentally different magnetic geometry:

Direct magnet slugs → each string got its own focused Alnico field.

Alnico V material → stronger, brighter, with faster transient response than Alnico II or III used elsewhere.

Fixed orientation → unlike adjustable screws, there was no “fuzziness” of magnetic spread.

The sonic result was tighter bass, sharper attack, and an unusually hi-fi clarity.

Jazz players could finally hear crisp articulation on the wound strings, something a stock P-90 sometimes smeared.

In a sense, the Staple was Gibson’s first attempt at precision pickup engineering.

Love It or Hate It

Yet the Staple was divisive.

For jazz-minded players, it was everything they wanted: articulate, clean, modern.

But for blues and early rock ’n’ roll players, it lacked the midrange growl and “hair” of a P-90. It sounded more polite, less feral.

By 1957, barely three years later, the Staple was gone from production. The Les Paul Custom moved to humbuckers, and the Staple became a footnote.

Why It Still Matters

Here’s the twist: the Staple wasn’t a failure.

It was a prototype in plain sight, a <a href="hardtail-vs-tremolo-does-the-bridge">bridge</a> between the raw P-90 and the refined PAF.

Lover was testing how magnetic geometry affects tone.

He was experimenting with individual Alnico slugs before combining coils to cancel hum.

The Staple proved you could engineer pickup response, not just accept it.

Without that detour, would the PAF have arrived as it did? Probably not.

Legacy and Revival

Original Staple-equipped Customs (1954–1957) are rare and collectible.

Reissues occasionally appear, and boutique winders still build Staple replicas for players chasing that articulate, hi-fi <a href="why-i-do-not-have-a-stiff-neck">neck</a> tone.

Listen closely: it is not simply a “brighter P-90.” It has its own fingerprint, articulate lows, shimmering clarity, less mud.

Plug one into a clean amp and you hear what Gibson thought jazz needed in 1954: precision instead of punch.

And in the broader arc of guitar design, it shows how every breakthrough, even the PAF, comes from experiments that almost get forgotten.

Takeaway

The Alnico V Staple is a reminder that guitar history is not just about the winners.

Sometimes the “lost chapters” matter more, because they show the process, the failed attempts, the stepping stones.

Next time someone tells you the story of the PAF, remember: before the humbucker, Seth Lover built a stranger, sharper thing.

It looked like a staple. It sounded like the future.