Today, coil-split and coil-tap switches are everywhere: from budget PRS SE models to Custom Shop Les Pauls. Pull a knob, and your humbucker pretends to be a single-coil. It feels modern. But this idea actually dates back to the mid-1970s, when Gibson quietly experimented with the circuitry that would later define guitar versatility.

This is the story of how that happened and why early coil-splits failed to catch on.

The Problem: Humbuckers Couldn’t Do Everything

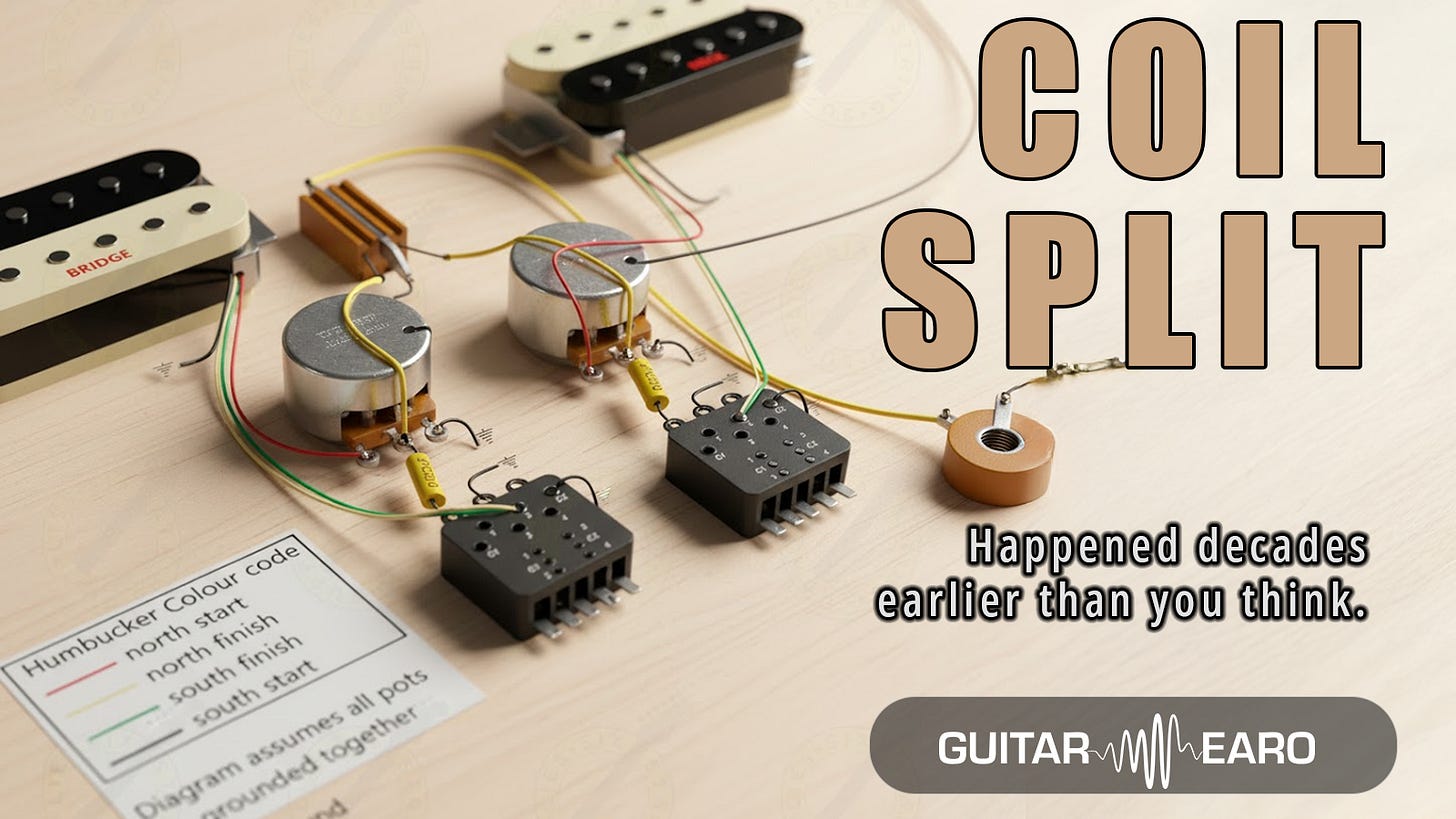

By the early ’70s, Gibson’s dual-coil humbuckers had long been the industry standard for power, smoothness, and noise-free performance. But they were also dark and compressed compared to Fender’s bright, articulate single-coils.

Session players wanted both characters in one instrument. Nobody wanted to haul two guitars to a gig or endure the hum of a single-coil under studio lights.

Enter a small group of engineers at Gibson Kalamazoo who began experimenting with multi-mode wiring, splitting coils, tapping windings, and adding filters to emulate the high-end chime of a Strat or Tele without losing the Les Paul body.

The First Production Coil-Split: Gibson L6-S Custom (1975)

Arguably the first production guitar to offer coil-split-like tones was the Gibson L6-S Custom, introduced in 1975. Designed by Bill Lawrence, it featured two “super-humbuckers” and a six-position rotary switch that rewired the <a href="high-vs-low-the-eternal-pickup-output.html">pickups</a> in various combinations:

Both <a href="high-vs-low-the-eternal-pickup-output.html">pickups</a> in series

Both pickups parallel

Neck pickup only

Bridge pickup only

Both pickups series out of phase

Both pickups parallel out of phase

Though not labeled “coil-split,” positions 2 and 4 effectively simulated single-coil brightness by changing inductance and phase relationships. The pickup coils were wound with lower resistance (~5.4 kΩ per coil) and paired with a 100 kΩ volume pot, a very un-Gibson value that kept highs intact.

Lawrence was trying to design a humbucker that could function like a pair of single-coils when wired creatively. He succeeded, at least on paper.

However, players expecting “Strat sparkle” found the result underwhelming: volume drop, thinness, and impedance mismatch made those bright modes sound anemic through vintage amps.

Early Coil-Tap vs Coil-Split: A Confusion Born at Gibson

Gibson’s marketing at the time blurred two very different electrical concepts:

Coil tap: drawing signal from a partial point of a single coil’s winding to lower output (seen on some lap steels and P-90 variants).

Coil split: disconnecting one coil of a humbucker to leave a single coil active.

The company sometimes called both “coil-taps,” leading to decades of terminology confusion that persists even in modern catalogs.

Technically, a coil-tap reduces inductance and output while keeping hum. A coil-split removes hum cancelation but produces the higher resonant frequency and sharper transient response of a single-coil.

Other Gibson Experiments: 1974–1978

1974 ES-345TD “Country Gentleman” (limited run): featured a true coil-cut mini-toggle, providing authentic single-coil operation in a semi-hollow format.

1978 Les Paul Artist: integrated an active preamp, compression/expander circuits, and a single-coil selector switch, effectively the first “active” Gibson before the B.B. King Lucille.

Prototype R&D boards from 1976–77 show Gibson testing coil-isolation circuits using CMOS switches rather than mechanical toggles, an early flirtation with electronic switching decades before PRS or Music Man would popularise it.

Meanwhile, independent brands like Carvin (then still family-run) were including physical coil-split mini-switches by 1978. These used a simple SPDT on-off configuration to short one humbucker coil to ground, the same topology later used in push-pull pots across the industry.

Why the 1970s Coil-Split Failed

Several factors doomed these early experiments:

Volume loss: a typical late-’70s Gibson humbucker measured 7.5–8.0 kΩ in series. Splitting one coil effectively halved the output, often producing a 4–6 dB drop.

Impedance mismatch: Gibson’s 300 kΩ pots and .022 µF tone caps were voiced for darker humbuckers. Once split, the circuit loaded the pickup excessively, dulling the treble the feature was meant to provide.

Noise: 60 Hz hum returned with single-coil operation. Unacceptable to players accustomed to silent humbuckers.

Cultural mismatch: ’70s rock players valued thickness, not brightness. The “Fender-like” voicing Gibson chased wasn’t in demand until the next decade.

As a result, the coil-split stayed a spec-sheet novelty, used rarely and misunderstood often.

The ’80s Revival: When Superstrats Made It Cool

By the early 1980s, hard-rock players wanted both heavy distortion and glassy clean tones. Brands like Ibanez, Kramer, and Charvel began offering “superstrats” with high-output humbuckers that could be coil-split via push-pull pots.

In that context, the concept finally made sense. Players could pull a knob to get pseudo-single-coil cleans between solos, or to brighten up chorus-laden parts.

The same topology that Gibson introduced as a curiosity became a selling point, and an expectation.

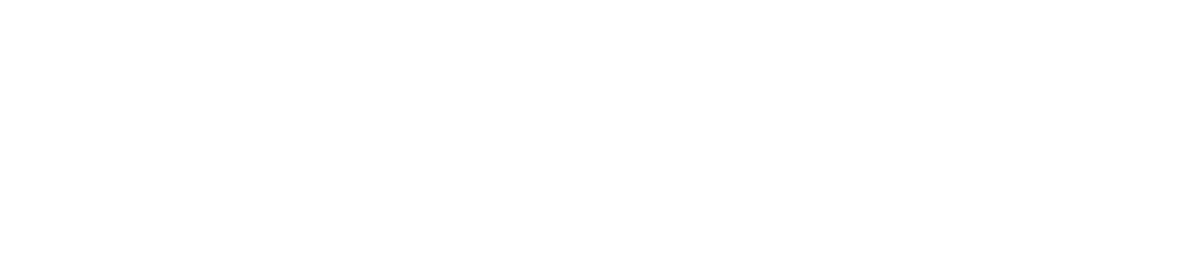

Electrical Anatomy of a Coil-Split

A modern humbucker contains two coils wired in series and out of phase magnetically.

When splitting:

A switch (often the push-pull pot’s DPDT section) connects the junction between coils to ground.

This shorts one coil, leaving the other active.

Inductance drops by ~50%; the resonant frequency rises by 1–2 kHz.

Output voltage falls roughly 40–50%.

Noise rejection disappears (single-coil hum returns).

To compensate, some modern designs use asymmetrical coils or partial splits (with resistors in series) to retain body while still shifting the frequency response.

Bill Lawrence’s 1970s experiments were the embryonic version of this thinking.

The Legacy

The coil-split taught builders two lessons that reshaped electric-guitar design:

Versatility sells. No pickup type satisfies every tonal need.

Circuit design is tone design. Players learned that wiring, not just magnets and wood, defines a guitar’s voice.

Today, nearly every manufacturer offers coil-split or coil-tap functionality. The irony? Gibson, the company that invented it, spent decades downplaying those very features in favour of vintage purity.

Why It Matters

For tone purists, the coil-split is more than a switch: it’s the moment electric-guitar electronics turned modular. It acknowledged that the guitar signal path could be a design space as rich as the wood and hardware.

The 1970s Gibson engineers who chased “Fender sparkle” inside a humbucker didn’t just fail at mimicry. They created the DNA for the Swiss-army guitars we play today.

Key Technical Specs and Models

Epilogue

The next time you pull a push-pull pot to make your Les Paul “quack,” you’re not engaging some modern feature: you’re triggering half a century of failed experiments, rewired and perfected.

Gibson’s mid-’70s flirtation with coil-splitting might not have sounded glorious, but it quietly defined the idea that one guitar can contain multiple tonal identities.

In an age obsessed with vintage correctness, that remains the most radical idea of all.